A Personal History of Shea Stadium, part five

Dwight Gooden enters rehab; Dick Young demands the city "Stand Up and Boo" at his return; Spiderman gets married at home plate; Gooden comes home to Shea; "Dick's a Pest, Dwight is Best"

Enjoy this occasional series, weaving together my life in NYC with the vicissitudes of baseball as it was played within the brutalist-adjacent concrete walls of Shea Stadium.

part 1 | part 2 | part 3 | part 4 | part 5 | part 6 | part 7 | part 8 | part 9 | part 10 | part 11

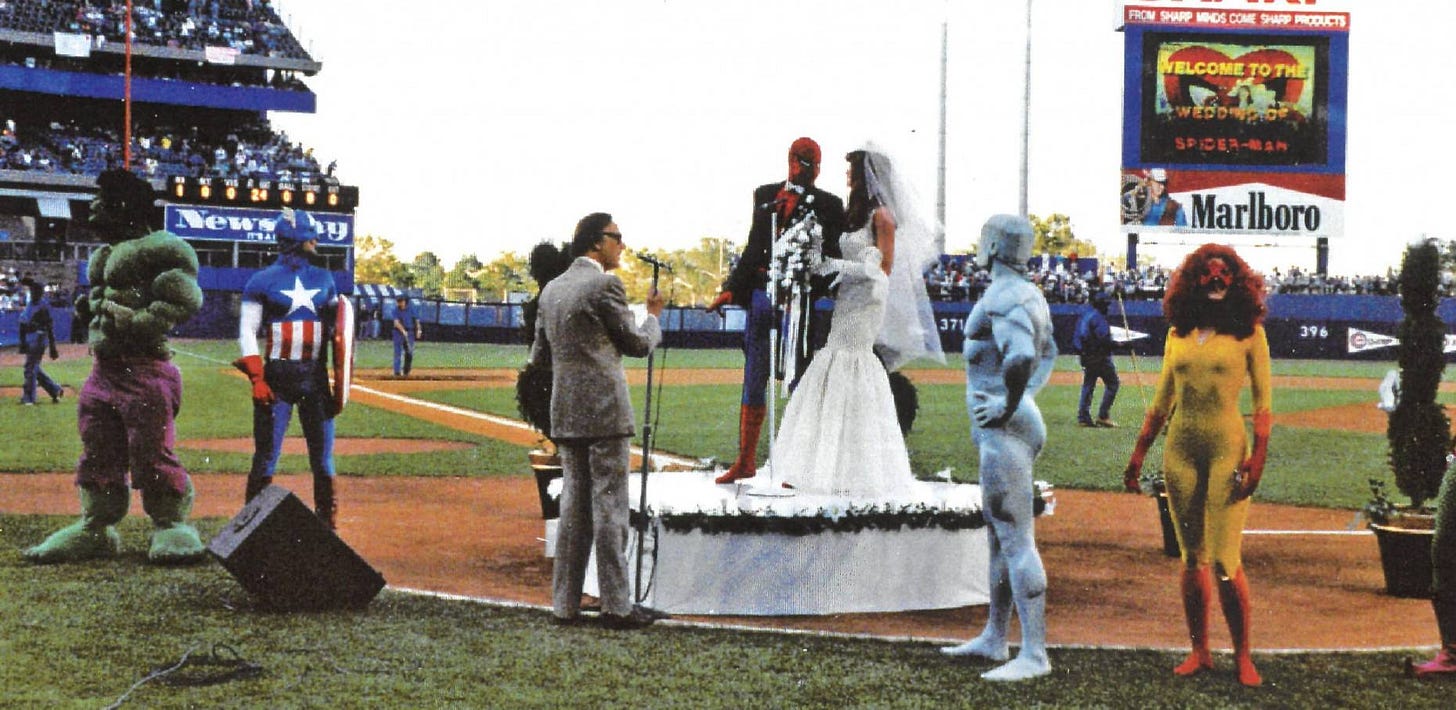

Spiderman’s Wedding

The Mets won the World Series in 1986, two years after Dwight and I found our respective ways to New York City. It was a team for the ages, with the best winning percentage ever for a Mets team, and one of the best in the history of baseball.

In 1987, the Mets were not nearly as good. There were numerous reasons for their decline; it is historically difficult for a team to win back-to-back World Series. In my mind, the biggest reason was obvious. Dwight Gooden had failed a drug test during the off-season, and Major League Baseball sent him off to a required rehab stint to help him beat a cocaine addiction. As a result, the Mets started the regular season without their ace pitcher.

Dwight Gooden returned to Shea Stadium on a raucous Friday night in early June. Coincidently, it was the same night Marvel comics was holding an outlandish promotion: Spiderman was getting married at home plate, right before the game. Shea was a circus. Planes flew overhead advertising fee admission to strip bars with a ticket stub. Beer flowed freely. The ballpark was sold out (we had to pay premium prices out in the parking lot for scalped tickets way in the uppers), and buzzing with excitement. Most people showed up a good hour or more before the game began (I know I did), soaking up the energy.

I’ve seen a LOT of baseball games. This was maybe the most fun I’ve ever had at the ballpark.

Even without Dwight’s return, Friday nights at Shea were crazy, and the wedding on the infield before the game started assured it would be crazier than usual. They handed out large-format promotional comic books and posters to everyone attending the game. Even before the game started, people—especially the people in the uppers—began tearing up the comic books and posters and flinging the scraps out onto the field, like confetti. I don’t think anyone planned on that happening, though they should have. Torn up paper floated down onto the field all night long. Our seats high in the rafters were a great vantage point to watch confetti float across our field of vision, superimposed over the bright green grass and those improbably blue walls.

In retrospect, I wish I’d kept my comic book, but I ripped mine apart and flung it over Shea, just like everyone else.

Meanwhile, culture wars (yes, the 1980s had culture wars too) were circling around Gooden’s return. A popular old-school newspaper sports writer named Dick Young published a column in the New York Post that morning titled, “Stand Up and Boo.” The column was an act of hateful performative outrage, where he urged his fellow New Yorkers to boo Dwight Gooden at his return that night, as his return to baseball after testing positive for drugs glorified drug use.

If anyone boo’ed Dwight that night, I didn’t hear them. Shea Stadium that night was a giddy love-fest. We recognized Dwight’s return for what it was, a fresh start for a talented young man who had been victimized by drugs. The lesson it taught was not one of glorified drug use, but rather the value of forgiveness and hard work and second chances. We had friends in the same position Dwight was in. Again: he was one of us.

A fan in the upper deck brought along a sign that said, “Dick’s a Pest, Dwight is Best!” and he walked the length of the walkway at the base of the steps like a flag-bearer on the field of battle. The crowd cheered him every time he passed by. The recurring sight of that sign is my most vivid memory of the night. Even now, decades later, it brings a smile to my face. He waved that flag from well before the game to well after.

Before the first pitch could be thrown, however, there was a wedding to attend. Spiderman and Mary Jane Watson stood behind home plate. Captain America served as Best Man. Stan Lee officiated. The Green Goblin, Iceman, and Firestar were also trotted out (I’ve never heard of the last two). This was before any of the Spiderman movies, before the Marvel Universe, before Stan Lee had become a household name.

The crowd gathered for the game was buzzing, but didn’t show a great deal of interest in the ceremony taking place on the field. The noise level remained fairly constant. It might have ticked up slightly when Mr. Lee said, “I do,” but not by much. The wedding was fun, and all the free stuff the gave us was cool, but it was pretty obvious that folks weren’t there for the wedding. We were there for Dwight.

Dwight Gooden’s return to baseball took place in front of a cheering and adoring crowd on June 5, 1987. The crowd stood and cheered as he walked to the mound. The first pitch he threw was a strike. The crowd went bonkers in response. I don’t need to look it up; that first pitch is burned in memory.

The Pirates went down 1-2-3 in the top of the first. The Mets scored twice in the bottom of the first, and there was no going back. The rest of the game is a blur, an evening filled with fun and joy and simple summer pleasures. The Mets won, 5-1. I’d thought the score was more lopsided; I suppose it shows my youthful confidence in victory.

That game also marked the beginning of the second, less dominating era of Dwight Gooden’s baseball career. He never again won 20 games, though he remained an effective pitcher for the next eight years. In 1992 and 1993 he posted his first losing records. 1n 1994, at the age of 29, 10 years after he broke into the major league, he tested positive for cocaine and was given a 60 day suspension. In 1995 he was again suspended from baseball for drug use. He never pitched for the Mets again. Even more galling to the Mets faithful, he signed with the Yankees and pitched a no-hitter for the pinstripes.

It's easy to blame the sharp decline in his abilities on drug use, and drugs may be deserving of blame. Drugs certainly deserved the blame for much of the wasted lives I witnessed in the heady days of 1980s Manhattan.

During the glory years of the mid-eighties, Dwight Gooden and Darryl Strawberry, good friends, the ace of the pitching rotation and the clean-up hitter, arguably the two biggest stars of the Mets, were expected to be the Micky and Whitey of their time (referring to Micky Mantle and Whitey Ford of the Yankees in the 50s, also good friends, also the ace and the clean-up hitter). It is hard to know what is real and what is hyperbole, but the exterior resemblance holds.

Dwight and Darryl never lived up to their young phenom potentials, though they certainly had successful careers in baseball (both of them had their numbers retired in 2024). Daryll hit over 300 home runs and plated exactly 1000 RBIs. Dwight won 194 baseball games and posted a 3.5 ERA (three and a half runs per game).

Both men signed with the Yankees at the end of their careers, and Dwight even threw a no-hitter for them. You are correct in assuming how much it galls me that he did this as a Yankee.

#

Dick Young died later that summer, in August 1987, of natural causes. In his obituary, the New York Times described Young's prose style as having "…all the subtlety of a knee in the groin. Dick Young made people gasp... He could be vicious, ignorant, trivial and callous, but for many years he was the epitome of the brash, unyielding yet sentimental Damon Runyon sportswriter."

Esquire called Young's writing "coarse and simpleminded, like a cave painting. But it is superbly crafted."

He’s in the Baseball Hall of Fame, mostly for being the first reporter to go into the clubhouses and make that part of reporting the game. But Mets fans remember him for different reasons entirely.

In addition to the whole “Dick’s a pest / Dwight is Best” debacle, Mr. Young once described Mets ace Tom Seaver, a three-time Cy Young Award winner and perhaps the most beloved figure in the fifty plus years of Mets history, as "a pouting, griping, morale-breaking clubhouse lawyer."

Tom Seaver? Seriously?

Sportswriter and baseball historian Marty Appel goes even further than the NY Times and Esquire. Cringe at this bit of forgotten history: “[Young] pretty much ran Tom Seaver out of town, writing a column defending the Mets and suggesting that Nancy Seaver and Nolan Ryan’s wife Ruth had a jealousy going. Seaver called it “the last straw.” [Young] wrote a note about why Johnny Bench’s first marriage ended that made even Young’s best defenders wonder if he had gone too far.”

Go into any sports bar in New York City. Ask for a show of hands. How many of them remember Dick Young? Then ask: how many of you remember Dwight Gooden? How many of you remember Tom Seaver?

You already know the answer.

A hero gives us the gift of a larger life, for as long as they can manage the tightrope between the public and the private. New York City remembers its true heroes. The rest is just footnotes.

Peace.

To be continued…