A Personal History of Shea Stadium, part seven

What to sing on the 7 train after a Mets game; I acquire season tickets and a brief unrequited crush; Vince Coleman throws firecrackers at Mets fans while Bret Saberhagen squirts bleach at the press

Enjoy this occasional series, weaving together my life in NYC with the vicissitudes of baseball as it was played within the brutalist-adjacent concrete walls of Shea Stadium.

part 1 | part 2 | part 3 | part 4 | part 5 | part 6 | part 7 | part 8 | part 9 | part 10 | part 11

More snapshots from Shea Stadium:

On my birthday one year, several of us went to see a Mets game. The seats are the primary thing I recall about this visit to Shea. We were in the very last row, right up against the metal of the bright blue backing, and if you turned around you had a great ariel view of the parking lot. The view of the ballfield was typical Upper Deck birds-eye view, but the place was full, and the air expectant.

The scarcity of seating tells me it had to have been a nearly sold-out game, which pins the date at 1987 or 1988. I was excited to be there, and received quite a few free birthday beers.

My recollection of Kevin Elster hitting the winning home run late in the game points me to the correct game almost immediately on the internet: July 29, 1988 (actually the day after my birthday). It was a great game: seven innings of scoreless baseball. 1-0 was the final score, and that lone run was hit by our shortstop, Elster, in the bottom of the 8th inning.

When the last out was made, our seats at the full height of Shea Stadium shook like we were at the top of a tree. It was a crisp, well-played game on a fine summer evening.

Both pitchers (Bobby Ojeda for the Mets and John Smiley for the Bucs) threw complete games, and each gave up exactly three hits. My kind of baseball.

The Mets won.

#

I’m looking at boxscores and old blogs and summaries of Mets games, but I can’t auger down to the specifics of this next memory. I’m with my friend John, and we are at a Mets game that is to be followed by a concert by some random, unknown band (I think it might have been Irish night, and the band Irish as well, though this has not helped me find the specific game).

The Mets get beaten up by the other team. Just walloped. Normally, this might mean that the crowd would disperse as the Mets fell further and further behind. But tonight, there’s a concert.

This means three things. One, no one is leaving. The crowd is sticking around, despite the score, in order to see the concert. Two, the crowd is in a surly mood. They are all watching their team lose, and badly. Three, they don’t cut off beer sales in the 7th inning, because of the concert.

By the time the game is over and the band takes its place on the undersized, makeshift Shea Stadium stage, the remaining crowd (including me) is drunk and surly. The band, frankly, is pretty bad, and utterly unable to command the attention of an entire stadium. Those assembled at Shea boo the band the entire time they play. I remember being embarrassed for them. The mood in the subway cars leaving the ballpark that night is sullen. No one is singing.

It’s an ugly night at Shea.

The Mets lose.

#

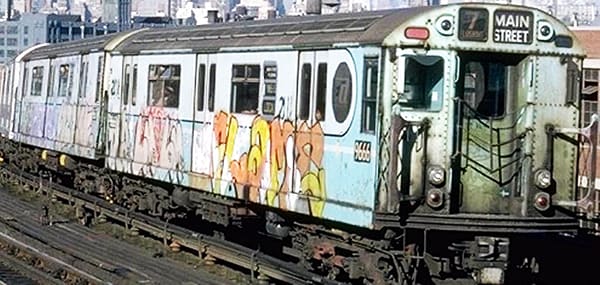

The 7-line trains leaving Shea after a loss are subdued and uncrowded, as much of the crowd has already left by the end of the game, and those who have stayed are not in a celebratory mood. After a win, the crowd tends to stay, and the rides home are boisterous and crowded and fun.

Shea is not the first stop on the 7 line back into Manhattan, so that by the time the subway train arrives, several riders are already in the car.

After a loss as Shea (statistically more likely than a win; with 4749 wins and 5108 losses, the Mets' all-time regular season winning percentage is .482, or 48% of the time), the oncoming riders are pretty relaxed.

After a win, the riders approaching Shea look scared. Why? Far fewer have left the stadium during a win, and so the Willets Point-Shea Stadium subway platform is full to overflowing. Hyped-up Mets lined up at the doorways two and three and four people deep. When the train arrives and the doors open, excited and beery fans rush into the breach, taking every available open spot, standing room only.

So, wearing that steely thousand-yard stare as they face down the sea of people about to invade the subway car, the riders inside the car secure their belongings, grab their handrails, and gird their resolve, steadying themselves for the oncoming tide of Mets fans.

A list of songs I’ve heard sung out loud by the celebrating crowd on the 7 train back home from Shea after a win:

Meet the Mets (of course)

Take Me Out to the Ballgame (of course)

Gilligan’s Island theme song

The Flintstone’s theme song (TV theme songs are a common theme)

Happy Birthday

Everybody Wants to Rule the World (a song heard so often in the NYC I lived in it might as well have been the city’s theme song, along with the Pogues’ glorious Fairytale of New York)

We Will Rock You

I Wanna Be Sedated (my personal favorite)

Who Let the Dogs Out (a truly embarrassing one-hit-wonder the Mets used as their official “anthem” in 2000)

Batman theme song

Friends theme song (mostly the clappy part at the beginning)

Cheers theme song

American Pie

A recurring issue with taking the 7 train back into Manhattan after a Mets game is the forty-five minutes it takes to arrive at the Grand Central-42nd St. station. Exiting the stadium, particularly after a Mets win, when everyone is pumped up, the general mood is to keep the party going, by hopping into a bar somewhere for a victory beer and some Sportscenter highlights. Sadly, there were no bars near Shea Stadium, a fact I never understood, as any bar situated near a stadium, even one as drab as Shea, would rake in tons of easy money. I assumed at the time that it was a zoning issue. It may have been, though I’ve read that the new Shea Stadium (or whatever they’re calling it) is surrounded by bars and restaurants. There’s talk of building a casino.

Back in the day, we had none of that. The closest bar that didn’t leave us stranded in the middle of Queens late at night was in Manhattan, nearly an hour away. Everyone might want to party when the game ends, but after an hour of riding the subway, everyone just wants to go home.

#

My last year in NYC, I had a budget season-ticket plan with my friend Simon. The plan, as I remember, was called the six-pack, and gave us a pair of seats for six games in the season. It was surprisingly cheap ($200-ish as I recall). We bought them in the winter of 95/96, and part of the experience was the option of going to Shea and actually field-testing your seats in the middle of winter. While the physical visit to Shea was optional, there was no way I’d miss it. The surrealism of sitting in a seat in the middle of an empty Shea Stadium while snow still lay on the ground is worth the price of admission.

That said, these were pretty good seats. They were high in the Mezzanine, but almost directly behind home plate. You could judge balls and strikes surprisingly accurately from the vantage point of those seat.

In 1996 attendance was low because the team was very bad. The Mets tried to pull more fans into the seats by promoting all the new and exciting foods available at Shea. First game of the six-pack, we went to the food court to sample the new fare. The gourmet food? Chicken tenders and curly fries! At the time it seemed like an embarrassment of riches. Compared to previous offerings, this was manna. I specifically remember expressing surprise at this brand new, fancy-pants, “honey mustard” dipping sauce that came with the tenders. Chef’s kiss!

#

One of the cool things about having a season ticket (albeit for only six games) was that you got to have the same seats for every game, and that the other season-ticket holders always sat in the same seats too. We got to know the other season-ticket holders in our section, by sight if nothing else.

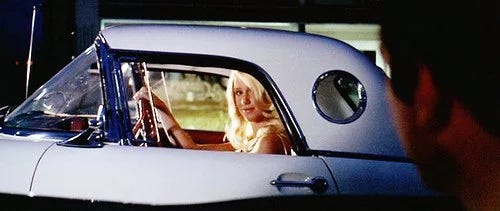

That’s how Simon and I met Tee Shirt Girl. I say met, but she was a few rows behind us, and mostly we just admired her from afar. She was pretty, and she had a predilection for tee shirts (thus the nickname; we never learned her real one). If you are of an age to remember the movie American Graffiti, you will grasp this reference: she was the unattainable Blonde in the White Thunderbird, representing the archetypical girl of Richard Dreyfuss’s dreams (played by Susanne Somers).

I spoke to her once. The following story paints me as inept when approaching women (and implicates Simon to a lesser degree), but I will attempt to tell it truthfully. We saw Tee Shirt Girl walk down the steep steps of the Shea Stadium Mezzanine, to get a beer, or a hot dog, or go to the restroom, or something. I jumped out of my seat. I wanted another beer, and saw a chance to talk to her.

I caught up with her just before the exit that leads out of the Mezz and into the ring of food and beverages stands. The was a slowdown just before the exit, where several aisles intersected. As we all stood, waiting to make our way out, she actually turned to me. This was my chance!

“Hi,” I said.

“Hi,” she replied.

That’s it. She turned again and took the exit out of the Mezz. I sheepishly turned and shrugged to Simon, who was watching, several aisles away. Then I followed along behind her.

I never spoke to her again (if you can call a two-word conversation “speaking”).

In my defense, Richard Dreyfuss never got to talk to Susanne Somers either.

I don’t remember if the Mets won or lost.

#

It is hard to over-stress how bad these mid-90s Mets teams actually were, so much so that the players began to slip into hostile, and sometimes injurious, behavior.

One player (Vince Coleman, well past his prime) threw firecrackers at a crowd. According to the ever-excellent Reddit thread about the Mets, “Coleman drove up in a car, opened the door and dropped what he believed to be a firecracker but was in actual fact an M-100…. The explosion burned three nearby bystanders, one of them being a little three-year old girl.”

Another player (Brett Saberhagen, having one of the worst years of his career after joining the Mets) filled a water pistol with bleach and fired at the New York press pool.

Bobby Bonilla became a Met in the 90s, at the tailing end of a long and productive career. His production had fallen dramatically by then, and his penchant for fighting with reporters and insulting the fan base resulted in the Mets paying off the remaining $6 million of Bonilla’s contract, just to get him out of the dugout. The Mets cut a bizarre deal that has them paying Bonilla a million dollars every July 1st until 2035. Mets fans now ruefully celebrate July 1st as Bobby Bonilla Day.

The Mets were a mess. The Mets are nearly always a mess.

They’re our mess.

Peace.

To be continued…