A Personal History of Shea Stadium, part four

The second dead man from Game Seven purposely falls down a long set of steps to gain access to pills; We meet for a drink years later; I hear conflicting accounts of his death

Enjoy this occasional series, weaving together my life in NYC with the vicissitudes of baseball as it was played within the brutalist-adjacent concrete walls of Shea Stadium.

part 1 | part 2 | part 3 | part 4 | part 5 | part 6 | part 7 | part 8 | part 9 | part 10 | part 11

Enjoy this occasional series, weaving together my life in NYC with the vicissitudes of baseball as it was played within the dull, brutalist-adjacent concrete walls of Shea Stadium.

part 1 | part 2 | part 3 | part 4 | part 5 | part 6 / part 7 / part 8 / part 9

The other dead guy watching game seven of the 1986 World Series was named Robert. He died decades ago. He was a talented man, and I directed him once in a play (written by Jim Uhls, no less, the man who wrote the Fight Club screenplay). Robert had a string of beautiful girlfriends, which in my less charitable moods I’d attribute to his easy access to cocaine (he was a bartender in downtown Manhattan, which was awash in the stuff), but he was good looking, and charismatic, and talented, so perhaps he came by those girlfriends honestly.

The last time I saw Robert I was living in Brooklyn. He called me, out of the blue (I hadn’t talked to him in years). He asked me if I wanted to meet up with him at a bar near my house.

“Sure,” I said. It sounded like fun, and I was excited to get to know how he was doing. The last time I’d seen him he was pretty strung out on pills and alcohol (he had a beautiful girlfriend then too, though she seemed to be more in the role of caretaker by that point).

I watched him twice—not once, but twice—purposefully hurl himself down a set of stairs in order to gain sympathy and, more importantly, access to pain pills once the EMTs came.

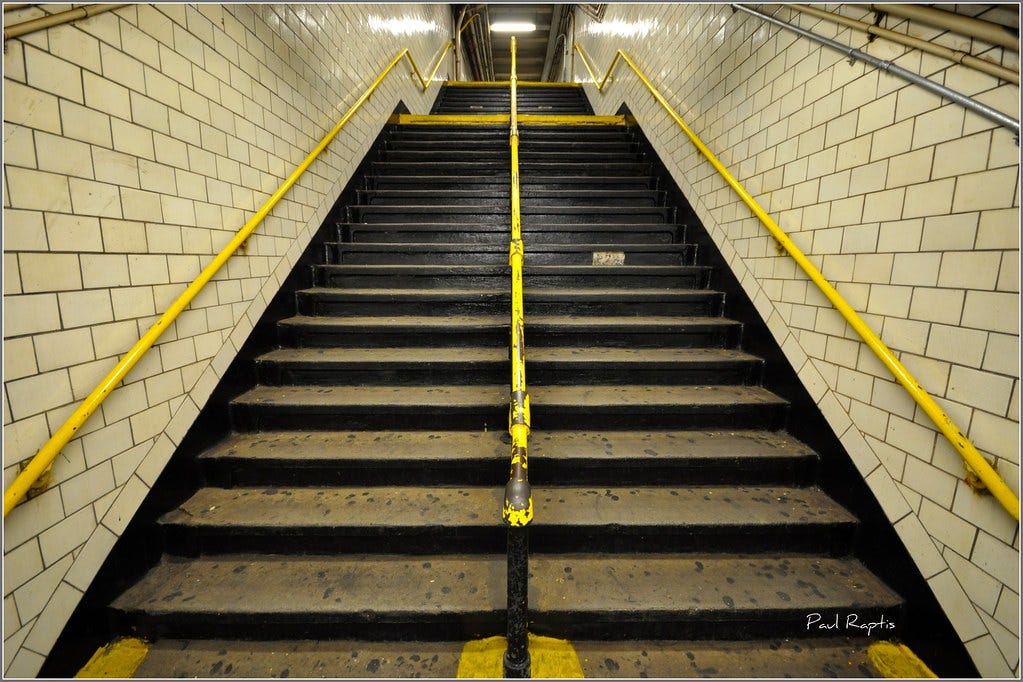

The first set of stairs he fell down was one flight, down the steps of the Brooklyn brownstone I lived in at the time. Those stairs were carpeted and only went a short distance. The second tumble down the stairs was harder, longer, and much more theatrical: down a long set of subway stairs at what I think was the 42nd St.-Bryant Park station. The stairs connected several subway lines and went down a very long way. I was arguing with him about not letting him stay on our couch, and I watched him make the decision, though I didn’t recognize it at the time: he stopped talking, straightened up, closed his eyes, and just leaned back. It couldn’t have been easy, convincing your body to ignore the several instinctual red flags keeping you from falling backwards into the possibility of extreme injury. It reminded me of those trust exercises in theater class, where you trust the group to catch you, the essential difference being that no one was there to catch him.

I ran down the steps, still not realizing the fall was probably on purpose; it’s just such a hard thing to believe. I called 911, waited for the paramedics to arrive. I took the subway to the hospital instead of going home, and spent a lot of time in the waiting room. When I talked to the doctor, I asked about Robert’s injuries. He gave me a look of pure incredulity, then softened, looked me in the eye, and said, “Your friend is drug-seeking.”

That was the moment I replayed his multiple falls down the stairs and finally put everything together.

#

Years later, I walked into the bar to meet him. I took a seat at the bar and ordered a beer. Robert was off in a booth by himself. He came over and took a seat next to me. Right away, the bartender’s reaction told me something was off. I got the sense Robert had been there for some time.

He ordered a soda and told me he didn’t drink anymore (this earned an eyeroll from the bartender, and I wondered if he was trying to warn me).

“I’m a drive time DJ down in Florida these days,” he told me. He had a good speaking voice, perfect for radio, so I didn’t NOT believe him. He looked very skinny though. A handful of times I thought I noticed his hands shaking. And there was that curious eye-roll from the bartender. So, while I was open and interested in his story, I was wary too. “It’s a good job, and I enjoy it.”

Okay. We exchanged a few more details of our lives. When he told me his wife had died, my bullshit radar went off.

“She died, two years ago,” he told me. “She died on Christmas Eve.” That was the exact point I heard the radar sound. “She had cancer, and it came to take her on Christmas. She died in my arms. She was the love of my life, Jeff.”

I think it was the accumulation of stock phrases that were dinging my red alarm sirens. Christmas Eve. Died in my arms. Love of my life. The use of my first name to encourage familiarity. The occasional cliché dropped in conversation means nothing, but when they begin to pile up, it has been my experience that someone is using words other than their own to tell me a story. If you can’t find your own words to tell me something important that happened to you, I am going to be suspicious.

I pretended sympathy. He might have been telling the truth; I had no proof he was lying. I had a full beer in front of me, and I decided I’d at least listen until my mug was empty.

I lasted through two empty mugs. The whole situation made me feel uncomfortable (though I admit the bartender’s barely veiled contempt when he looked in Robert’s direction may have had an effect). I believed him less and less. If you don’t believe the words coming out of someone’s mouth, it renders conversation beside the point. Nothing real is being communicated.

Robert stayed in the bar after I finished my second beer and said my goodbyes to him. He probably switched back to real drinks after I left; that was my assumption at the time (along with the assumption that he’d been drinking alcohol there before I arrived, and switched to soda on my arrival). I couldn’t wait to get out of the bar. Robert had been a good friend at one time, but I had to be honest with myself: I didn’t like him very much anymore.

He, too, was a talented man, along with Clif, along with most of the people I hung out with in those days. Many of them were successful in the arts, though most had side jobs to pay the rent. Talent isn’t uncommon. Talent plus the hard work necessary to turn ideas into concrete results is more rare. Talent plus hard work plus the good luck to be noticed is rarer still.

#

Clif, the first dead guy hanging out at the Richie-dome during game seven of the 1986 World Series, told me the same story Robert told me about how his wife died. In other circumstances, hearing the same story from two people would make me more likely to believe it.

In this circumstance, I assumed Clif heard the same story from Robert I had heard, and a sense of loyalty drove him to tell the story the way Robert had told it.

Another friend, John, who I messaged to try to get my facts right, told me he thought Robert died of a heroin OD in a Florida motel room. That story has the ring of truth about it. If anything, it’s too easy, and devoid of any detail that would allow you to get a firmer grasp of what might have happened. It seems too on the nose.

#

Unlike Robert, Clif lived much longer, and almost made his way out of addiction.

The last time I saw him, he had things together, or appeared to, anyway. He was sober, and living with his wife in L.A. They’d generously offered a room in their home when my family and I took a trip to L.A. to see a few friends and relatives, and of course, visit Disneyland. He was writing and acting again, and his work was at a high, professional level. He had the talent to make it, and was being noticed by others in the industry. His intelligence and thoughtfulness impressed me, and washed away much of the resentment of the Generations fiasco.

We all had a nice time in L.A, and Disneyland, and Clif and his wife were very gracious.

It didn’t last. Clif started drinking again, left his wife, and dropped a handful of extremely promising projects. I don’t know where he ended up, but he died of a heart attack.

I don’t mean to speak ill of the dead.

I’m trying to write down my unfiltered memories, accurately and truthfully. This is the result.

The takeaway from these stories about my two dead friends is sadness, at their deaths, at the waste of time and talent and abilities, the debris of broken friendships, the artistic compromises forced upon them by hangovers and drug-seeking and the unending need to tamp down whatever demon was taking up real estate in their minds.

I’ve wasted time and talent and abilities too. I’ve had those hangovers, sought those drugs. Demons take up valuable mental real estate every day of my life; I sometimes begin the fight as soon as I awake.

I don’t know why those two men are on one side of these words and I am on the other. Much of it was a matter of degree; all of us had addiction coded deep in the minutia of our DNA, mine had a little less hold on me than theirs did on them. Much of it was a matter of luck and timing. I do not think it is, or ever was, a reflection of character.

I miss you, Clif. I miss you, Robert.

That’s all I wanted to say.

Peace.

To be continued…