A Personal History of Shea Stadium, part eleven

The hole in the heart of New York City; I stumble into the end of a wake; Family exerts its pull from thousands of miles away; The Pushmepullu of loss and hope

Enjoy this occasional series, weaving together my life in NYC with the vicissitudes of baseball as it was played within the brutalist-adjacent concrete walls of Shea Stadium.

part 1 | part 2 | part 3 | part 4 | part 5 | part 6 | part 7 | part 8 | part 9 | part 10 | part 11

In 2006, I came back to Shea Stadium one last time.

Much had changed. By this time, I was working for the Colorado State University, married, living in Colorado with my wife and our two adopted daughters, aged three and five. By travelling to New York, I was leaving a whole other life behind.

As a reflection of that, most of my memories of the trip are not of the game. My focus had shifted to different concerns. In simple terms, I suppose I had gotten a life. I missed my wife, and I missed my kids.

My heart leapt as my plane circled Manhattan, seeing that charred hole in the beating heart of the financial district where the World Trade Center used to be. It was a visceral reaction to an unexpected sight, and I remember it vividly. I mourned my twin losses: the public loss of the World Trade Centers, and the private loss of my sister, who died by her own hand nine days after 9/11.

My heart leapt, but it landed at LaGuardia with the rest of my body. I made my way to New Jersey, where my fried Francis and his wife had relocated after winning a small sum on, and I am not making this us, Who Wants to be a Millionaire? (As an aside, after answering several questions correctly, Francis decided NOT to be millionaire on the show and kept the money he’d already won, rather than take up a question whose answer was…wait for it…the Oort Cloud!)

I spent much of the week in New Jersey with Francis and his wife. We’d travel out to Brooklyn and Queens and Manhattan, but always return to New Jersey. It seemed like, for this last trip, I was keeping New York City at a slight distance. We watched two games of the series in a New Jersey bar around the corner from his house, rather than travel to the epicenter of the series in NYC (the bar made some of the best from-scratch pizza I have ever tasted).

#

I travelled to Brooklyn several times during that trip, during the day, by myself, revisiting old haunts. I walked so much I had blisters by the end of the trip. I sensed it was the last time I’d visit Brooklyn for a long time (in fact, I haven’t been back since). I visited a couple of my old neighborhoods, in Park Slope and Greenpoint. I walked across the tiny little drawbridge on Greenpoint Ave. that traverses Newtown Creek, one of the most polluted waterways in the nation. I used to walk across this weird little bridge to get to the 7 train, and it is one of my favorite places in NYC.

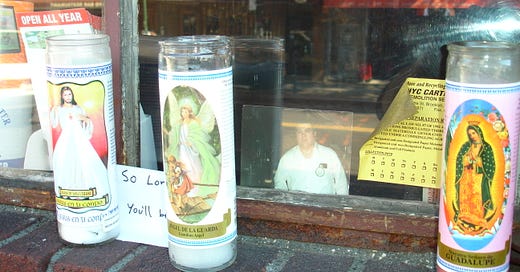

I visited an old bar I used to frequent: O’Conner’s, in the heart of Park Slope (this was before the neighborhood had fully gentrified). As I approached the familiar entrance, I noticed a small grouping of objects near the corner of the window. Three large glass votive candles, the kind with a picture of a saint on the front and ubiquitous in Brooklyn bodegas, were set across the ledge of the window (I’m looking at a picture I took of it at the time, trying to describe it accurately). Behind the candles, but in front of the glass of the window, exposed to the elements, was an index card. I can’t make out all the words, but the visible words said, “So long, we’ll miss you.” To the side of the car was a photo of Pat O’Conner.

Pat O’Conner was the owner of the bar. He’d inherited it from his father, and had been working behind the bar for decades. I wouldn’t say I knew him well, but I knew him. He was a good man. Irish, conservative, friendly, kind, religious. He had a front-row seat to the changing faces of Brooklyn, and was an encyclopedia of information about the local neighborhood.

That day in 2006, at the bar, I met Pat’s son, the man who would be taking over the bar from his father. He told me he’d been drinking for three days, ever since his father’s last breath. The bar had been the location of an extended neighborhood wake. Walking into O’Conner’s, you could feel the sad, defeated, exhausted energy in the air.

A beer and a shot glass sat in from of him. I asked him if I could buy him a drink. He considered it, then put a coaster over his beer glass (a sign, in Brooklyn bar-speak, thar he didn’t want a refill) and said, “No thank you, I’m done.”

He didn’t move from his spot, nor did he order another beer. I offered him a few short words about how much I respected his Dad, but otherwise let him be.

He looked a lot like his father in that moment.

I am reminded of the opening line of Richard Nixon’s autobiography: “I was born in the house my father built.” I mean this unironically: it’s one of the most evocative opening lines in literature, right up there with “Call me Ishmael.” I feel that I too, was born in the metaphorical house my father built, and the thought fills me with pride.

I stayed at the bar for a second beer, then made my way to the subway, and then to the LIRR, and finally back to New Jersey, and Francis’s house.

#

I visited the the ongoing construction work at the wreckage of the World Trade Centers while I was there. This was 2006, so the building that went up to replace them—the “Freedom Tower”—had not yet been built. The site of the 9/11 attacks was a large, ragged hole.

The subway through the financial district went almost directly into the site of the wreckage, circling along the jagged edge of the hole left in the city, so that subway riders could clearly see the construction workers readying the ground for a new tower. This had to have been by design, I think; it couldn’t have been that difficult to shield the wreckage site with plywood or sheeting. They left it open—I think—so that the sight of it was woven into the everyday lives of New Yorkers. When the subway car I was riding in entered the site, everyone in the car seemed to pause what they were doing. They lowered their newspapers, quit begging for spare change, quit scrolling their phones. Conversations died down to a hush. To New Yorkers, this was a holy area, and deserved respect. New Yorkers do not give respect easily.

I got off the subway in the financial district, and observed the spot some more. The place was thick with emotion. Memorials were everywhere. Teddy bears and handwritten notes and photos and flowers and balloons. My mind was split by these twin tragedies, inextricably linked, one very public, once very private: 9/11 and the loss of my sister nine days after 9/11. I shed a tear or two. Before I got back on the subway, I bought a rose from a vendor and wove it through the plastic net that surrounded the sides of the area, one rose among several hundred more. I left the flower there, along with a piece of my heart.

#

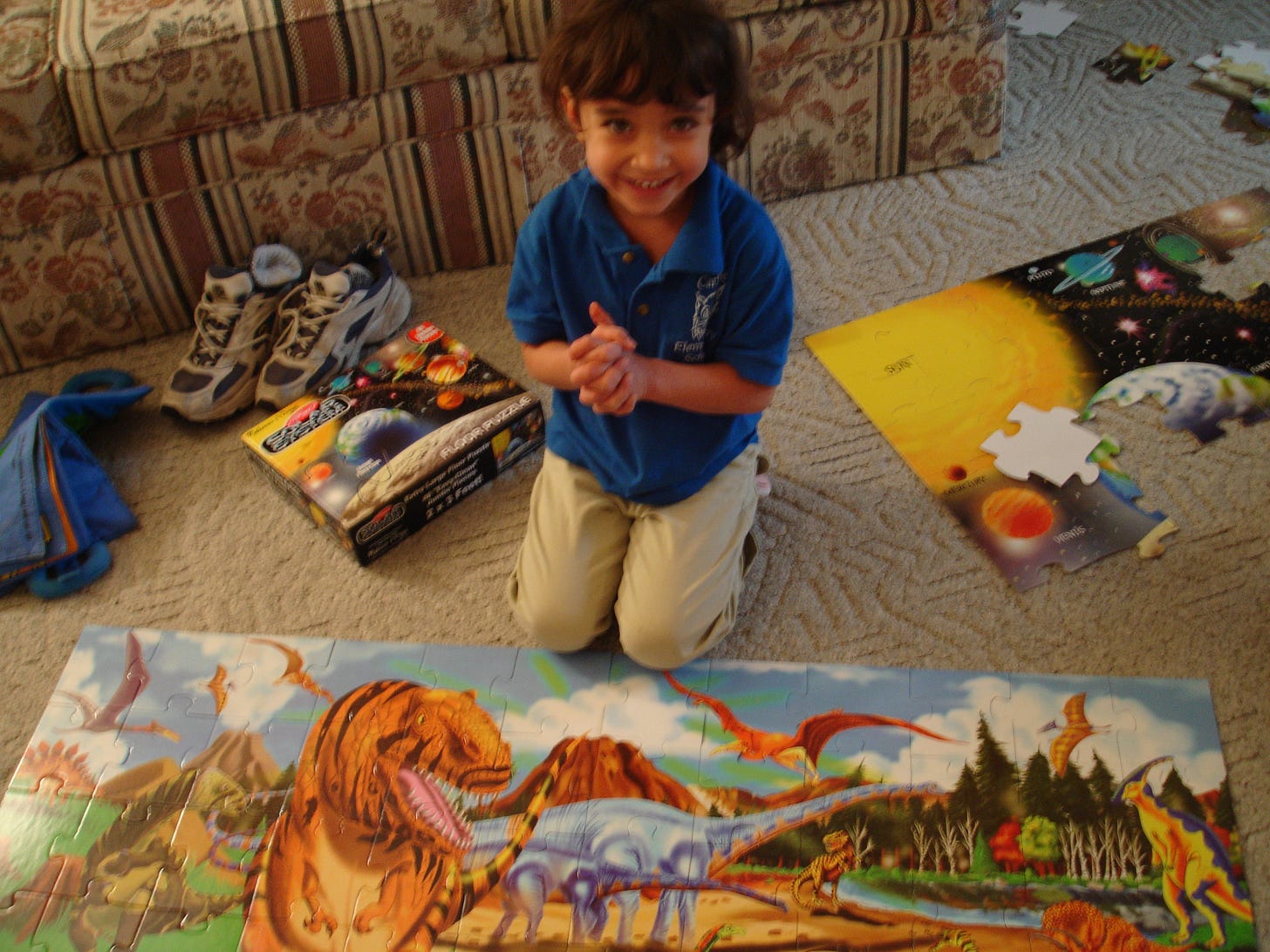

One of the goals in the back of my mind while in New York City in 2006 was to get my kids a good present for my return home. I looked over the gift shop at MoMA and found nothing. The Museum of Natural History had all those dinosaur skeletons, which were magnificent, but I couldn’t take them home.

I finally found what I was looking for at the Hayden Planetarium. The place has been around since 1935, but the new addition with the trippy six story cube with the sphere floating inside it wasn’t built until the year 2000. I’d never been there.

A couple hours later, after a tour and a planetarium show (I’m a sucker for planetariums), I left the planetarium with two boxes under my arms. Giant jigsaw puzzles, one of dinosaurs, one of the solar system.

#

I don’t have a huge store of memories of the game itself, which is a little odd, but also in keeping with the tenor of the rest of the trip. The game was Game One of the NLCS, the series that decided who from the National League would move on to the World Series. We had seats on the first base line, which was rare. In addition to Francis and I, a friend of Francis’s and her son attended.

The primary thing I recall about the Mom is her parenting style (assumedly because I was now a parent). I’ll preface this by saying that her boy was perfectly well-behaved, and a good kid, with an uncanny memory for Mets lore. That said, she told me that her and her partner had decided that they would parent without ever telling their child, “No.” I remember this primarily because I was telling my kids “No” pretty much constantly, and I couldn’t figure out the logistics of a yes-only household.

She patiently explained the details to me, right in front of the boy. I never heard her say “No” to her son during the game, nor did she ever have occasion to. Francis and I didn’t either. He was a good kid.

I’m surprised when I look up the details of the game. I remembered that the only runs scored were from a two-run homer from Carlos Beltran. I didn’t remember that the home run occurred in the bottom of the ninth inning as a walk-off home run. It’s odd I didn’t remember such an important detail. My mind was elsewhere. I missed my family.

I may not have remembered that Beltran hit as a walk off home run, but I do remember the important things. I remember the entire crowd rising as one, and the deafening roar that followed. I remember the long high parabola of the arc of the ball over the right field fence. In most cases I’m a little snobbish about the value of home runs in the game of baseball. I prefer the stolen base, the strategic hit-and-run, the ball in the alley that splits the outfielders and rolls toward the fences as the runner sprints to second base.

It's impossible to deny the trill of the homerun, however. It’s not even the instant runs scored that lay at the heart of the appeal of a home run. It’s the crazy beauty of that arc over the fences of the ballyard and into the night. The sight appeals to the imagination because the metaphor is so simple and potent: the ball leaves the ballpark and enters into another realm where we, the spectators, are not allowed.

The ball clears the fences. The confines of the white chalk lines are overcome. A hero shares with us the gift of a larger life.

#

My Dad died in 2020. He lived with my family and I for the last ten years of his life.

In that time, we watched a thousand games.

Now, when I watch baseball, it’s usually alone, though my wife is almost always a few feet away, at the kitchen table. I watch the game alone, but it feels like my Dad is sitting right next to me. His presence is not ghostly, or grief-ridden. We talk about the minutia of the game. We root for our team. Sometimes we exchange high-fives, which my wife notes with sympathy and quiet amusement.

#

I never returned to Shea Stadium after 2006. Shea Stadium never again hosted a post-season game. I saw the last series. By this time, my life had relocated and taken root. In addition to a wife and kids and a home, my parents had moved to town. I had a lot of people to take care of, and less time for things like flying across the country to catch a game.

The only baseball stadium I went to regularly after that was Coor’s Field, the ballfield where the Rockies play, in the heart of downtown Denver. It’s a lovely stadium, all girders and red brick, with the Rocky Mountains visible from the nosebleed seats. Whenever I went there, I felt guilty, like I was cheating on my first love, Shea Stadium, with a much more attractive partner.

My Dad and I watched Mets baseball together, from his living room couch, or from mine. My kids were often around, if not exactly watching the games, then aware of their presence, as background noise, like living next door to construction. They learned who Mr. and Mrs. Met were, what the Home Run Apple was, and what caused it to rise out of the top hat beyond the right field fence. They learned about strikeouts, double-plays, home runs, stolen bases, and hit and runs. They learned about (but never witnessed) the hidden ball trick. I’ve never witnessed it either.

I tried to teach them the Infield Fly Rule, but the nuances of the rule escaped them.

Construction started on the new Shea Stadium in 2006, right next to the old Shea Stadium. In 2007 and 2008, you could occasionally see the new stadium rising from behind the walls of the old stadium during a game. My kids learned about the new stadium too.

And then, after a few maudlin ceremonies, and a few old men (who were younger than I am now) sharing memories and shedding tears, and a few dull documentaries about the history of the stadium that were shown during rain delays, it was over. Shea was gone.

Life moved on. In 2015, at the new Shea (I won’t refer to the stadium by its given name, as it’s been given the name of a bank), the Mets made it to the World Series, as my Dad and I watched from a thousand miles away. I even hung a Mets flag from our second-floor balcony.

The Mets lost to the Royals in five games.

#

It’s rare for a non-fiction sports-writing narrative to end on a loss, but I suppose that is what I’m doing here. Nearly all of this story occurs after the Met’s big World Series win in 1986. Since then, the Mets have lost more games than they have won.

This is not a story about winning. This is a tale told on the margins, as seen from the cheap seats of the Upper Deck, tinged with addiction and loss and regret. Death looms large in this narrative, with five deaths directly referred too, and others implied. Nearly all the baseball stories I tell—except for the ones at the very beginning, in 1986—end in defeat, ultimately.

The losses not are balanced by wins. Baseball is more about losing than it is about winning (especially if you are a Mets fan). The losses are balanced not by wins but by hope: the great arc of the ball toward the outfield walls. Often, usually, the ball falls short. The crowd’s cheer cuts off abruptly, dissipating into sighs and swears, as the ball falls anti-climatically into the outfielder’s glove as he stands on the warning track, just in front of the outfield walls.

But some nights, the ball’s arc off the bat takes it high and deep, into the central focal point of all those floodlights trained onto the field, like a good actor instinctively finding their best light at the center of the stage. The white of the ball turns into a dazzling brightness that not even a TV camera can capture. To the human eye imperfectly attempting to capture the sight, the ball appears larger than it actually is, and more radiant. It transforms into a blurred sphere of light, a tiny sun, heading toward the far wall of the park. That is literally my last memory of Shea Stadium in person: the arc of Carlos Beltran’s ninth-inning, game-winning home run. For one night at least, hope triumphs over loss.

Emily Dickinson talked of hope as “the thing with feathers,” and while I love those words, hope to me is a white sphere made of two identical pieces of cow hide, exactly 108 stitches stitching them together into one long endless seam, a perfect figure eight, a snake eating its own tail as it sails toward the outfield.

You rise from your seat. Your heart leaps, your sprit soars. Odds are, the ball will succumb to the laws of gravity, arc toward the ground, and be caught on the warning track. But sometimes, and often enough, the ball keeps travelling, beyond the fence and into the dark night beyond: going, going, gone.

It’s out of here. Elvis has left the building.

Peace.

The End