You Can't Get There From Here

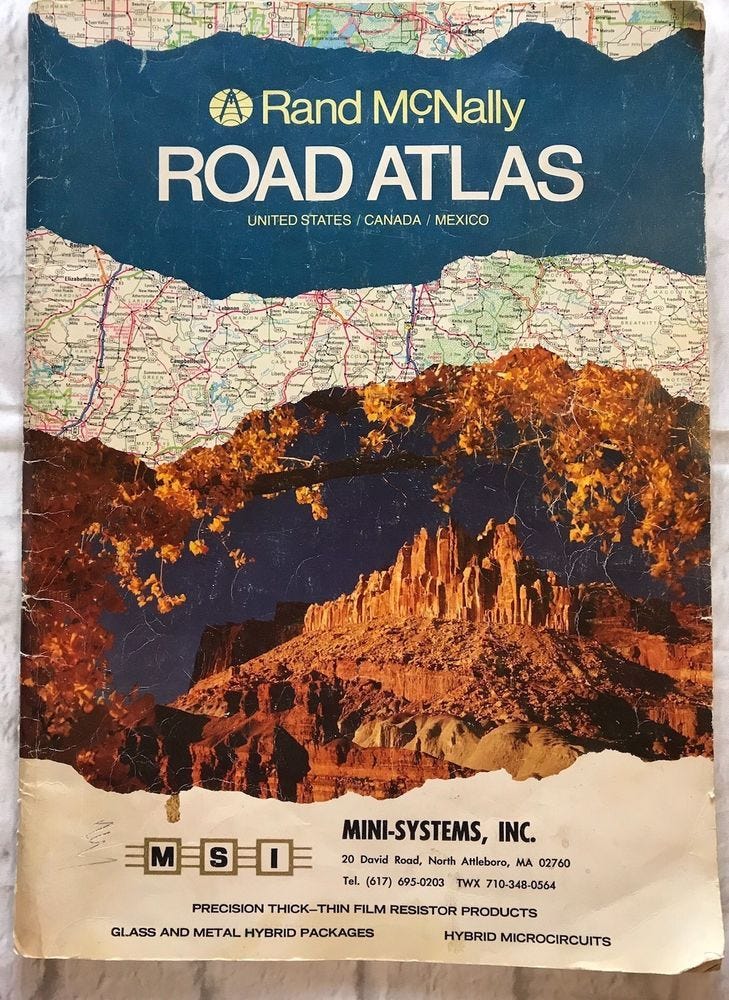

I have a beaten physical copy of the Rand-McNally Road Atlas bouncing around in the back of my soccer-Mom mini-van. I had one in the back of my Subaru I owned before that, and in my beloved Toyota pickup before that.

I’ve been looking at maps for as long as I can remember.

I remember when my family moved from Iowa to Arizona, driving ahead of the moving trucks, my sister and I and my Mom and Dad and my sister’s freaked-out Siamese cat. I followed along in the atlas as we drove, tracing highways and Interstates with my fingers as the miles droned under our wheels.

I remember sitting in my apartment in Minneapolis, bent over a map on the coffee table, planning a hitchhiking trip from Minnesota to New York City, via Canada, convincing myself it was something I could do, and I should do (I did).

I remember spending my first few weeks in NYC, taking the subway into Manhattan. I’d wander the streets all day long (and often all night long), vowing to get lost and find my way back to Brooklyn as a way of learning the city. I relied upon the heavily stylized subway maps that showed all the routes and all the stops. Even now, if I think of how NYC is laid out, my mind harks back to those simple color-coded lines. I don’t know the current NYC subway map, but that one was a densely-packed miracle, providing a great deal of information in a small space with skill and ingenuity.

I remember driving an old death-trap of a ‘65 Mustang at 100 miles an hour at like two in the morning on a desolate stretch of New Mexico highway in the Northeast corner of the state. When I think of that trip (Denver to Texas) I recall the map rather than the visual of the highway I was on.

I remember hiking in the Needles district of the Canyonlands with my (then) wife, using topographical maps to keep ourselves oriented. On our honeymoon hike we spent seven full days in the back country of the Maze district, where we depended on those maps for survival, making our way back to base camp every evening.

Trips to Texas. Trips to Chicago and Detroit. Trips to Los Angeles. My most recent outing, to deliver my Dad’s memorial in Oklahoma. All of them began with the familiar wonder of opening up a map—either digital or paper—finding the starting point, finding the ending point, and then examining the lines that connect them. Which is the fastest route? Which is the most interesting route? How many days will the trip take, and where are the best spots to stop for the night? As your questions multiply, the specificity with which you examine the map necessarily increases (which is one of the things I find so evocative about digital maps - that “pinch in” motion to instantly zoom in on a representation of the spaces you’ll actually be travelling to).

One of the dependably beautiful things about maps is that they are NOT the journey. They are a tiny detail of the journey, one of the more practical details that allows you to get from point A to point B. And as you accrue information about your journey from the map in front of you, an entirely new map forms inside your head: a timeline, day-by-day, of expectations and challenges and destinations. When the actual journey begins, the map is replaced by memory, a more complete and utterly personal recreation of the trip. That original map becomes obsolete: the framework of a much larger experience.

But you can’t take the trip without the map.

The map is where you begin.

Peace.

Commerce time. July’s story should be out at this time next week. I’ll forego the normal list of links and mention an upcoming reading: Stories Live! on July 21st (tomorrow!) at 7 p.m. I’ll be among a great group of writers. I’ll be reading a creepy little story called “Charlie Decides.” about an equally creepy game called “Charlie Charlie.”